The Federal

04 May 2020

A look at how discrimination has driven Chakma and Hajong tribes, refugees from Bangladesh, who settled in Arunachal Pradesh in 1964, to the brink of starvation and statelessness

Usha Moy Dewn, 75, hailing from the refugee community of Chakmas in Arunachal Pradesh, after days of battle with hunger, was handed over 10 kg rice on April 30, a day after the ministry of development of north eastern region (DoNER), concerned over reports of starvation among the Chakma and Hajong tribes prodded the state government to include the communities in COVID-19 relief programmes.

The DoNER’s intervention was a welcome relief, but not enough help for many below-poverty-line families like Usha Moy’s from the twin communities, which historically have been victims of discrimination and lately been facing acute hunger even since the nationwide lockdown was imposed.

Of the total population of Chakmas and Hajong, 30 per cent are daily wage earners and are in need of immediate relief.

All sources of the meagre earnings of Usha Moy and his wife, dried up after the government announced the nationwide lockdown, effective from March 25 onwards. The couple used to make a living by taking up odd jobs at Jyotipur, their village in Diyun circle of Changlang district.

Related news: In COVID-19 lockdown, desperation and hunger drive poor to the brink

“With no relief forthcoming from the state government, the couple were forced to ration their modest provisions by curtailing their daily food intake,” said Subimal Chakma, a community leader.

Their two sons, who live nearby, could not be of much support either. They too have lost jobs due to suspension of all non-essential services across the country to prevent the spread of the virus, and are also excluded from the government’s relief plan. The third son is stuck in Tirupur in Tamil Nadu.

Usha Moy, when reached over the phone of one of his neighbours, on Saturday (May 2), said, in relief he got only rice and nothing else. His extended family of sons and grandchildren did not get anything.

Past of persecution, pain of statelessness

Surprisingly though, the septuagenarian was not grumbling. He had seen worse, being a victim of discrimination all his life.

For the past 56 years, Usha Moy and most other members of the 65,875 strong Chakma (accounts for 90 per cent of the population) and Hajong communities, settled in the districts of Changlang, Namsai and Papum Pare, have been leading a stateless existence and facing discrimination on a regular basis.

The discrimination preceded their settlement in India in 1964. They started facing religious persecution in the then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, after India’s Partition in 1947. The Chakmas, who are Buddhists, hail originally from the picturesque Chittagong Hill Tracts, in south-eastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar.

They were subsequently displaced when their land was submerged under the gushing water of Karnaphuli River following the construction of the Kaptai Dam in 1962. The far-reaching impact the hydel-power project would have on the surrounding villages was not taken into account.

The Hajongs are Hindus. They fled East Pakistan’s Mymensingh district during 1964-1969 purely because of state-sponsored religious persecution.

Usha Moy was among the 14,888 refugees, comprising 2902 families, that crossed over to India, in waves during that five-year span. Some of them initially took refuge in Tripura while others in the then Lushai Hills district (present-day Mizoram) of undivided Assam.

“It took us seven days of walk through jungle tracts to reach the nearest bordering village in Tripura from our native village Babusara in the CHT,” recalled Purno Kumar Chakma (70), who had embarked on the arduous journey with his parents as a 14-year old.

Growing roots in India

The migration came close on the heels of India’s defeat in the war against China in the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) sector in 1962. So, the Union government felt it would make strategic sense to populate the vast vacant land in the NEFA, which morphed into a Union territory of Arunachal Pradesh in 1972 and a state in 1987. The Chakma and Hajong refugees were given settlement between 1964 and 1969 in present day Changlang, Namsai and Papum Pare districts. Almost 90 per cent of the population now live in five circles of Changlang.

A government letter dated April 21, 1965 on resettlement of the two communities, pointed out that, for an area of 33,000 square miles, the NEFA has a total population of just 3,37,000 people.

“We were brought to NEFA in batches in trains and trucks. Initially, a group of Chakma refugees were also taken to Bihar. Later, they were brought back to the NEFA for settlement. Every family was given three to five acres of land based on their size,” Purno Kumar recollected.

The land did not ultimately amount to much when divided up among the next generation, Purno Kumar clarified. Many people such as Usha Moy also lost their arable land to soil erosion by the Noa Dehing River, a tributary of the Brahmaputra.

Nevertheless, the land was fertile and the displaced people were willing to toil extra hard to rebuild their life, he remembered.

Soon clusters of bamboo-wall- thatch roofed huts, perched on stilts, were built on forest clearings as the new settled communities were digging their roots. Purno Kumar, Usha Moy and many others, who were in their teens or in twenties, soon got married and started raising families.

Related news: States fail to identify hungry under law even as hunger looms large

“There was no problem until the 1980s. We were getting rations, jobs and other benefits from the government. It never occurred to us then to push for our citizenship,” said Santosh Chakma, general secretary of the Committee for Citizenship Rights of Chakmas and Hajongs of Arunachal Pradesh.

Branded foreigners

Taking a cue from the anti-foreigners agitation of 1979-1985 spearheaded by student groups in Assam, their counterparts in Arunachal Pradesh started demanding eviction of Chakmas and Hajongs from the state, dubbing them as foreigners.

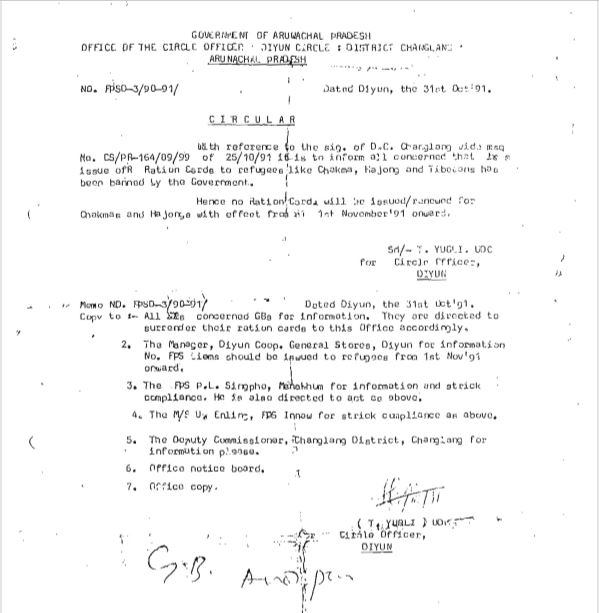

Bowing under the pressure, the Arunachal Pradesh government on October 31, 1991 vide a circular issued by circle officer, Diyun ordered that no ration card will be issued or renewed for Chakmas and Hajongs with effect from November 1, 1991.

Not only that, even granting of citizenship and voting rights to the Chakmas and Hajongs continued to be stonewalled despite the Supreme Court’s directives. Only 5,097 of 65,875 Chakmas and Hajongs have voting rights, the Arunachal Pradesh government had revealed in January this year.

“For the last 56 years, Chakmas and Hajongs have faced discrimination as a matter of state policy,” said Suhas Chakma, director of the New Delhi-based Rights and Risks Analysis Group (RRAG).

He said the exclusion of the communities from the COVID-19 economic package was part of that discriminatory policy.

Taking note of allegations of “massive hunger and starvation” faced by the two communities during the national lockdown, DoNER’s joint secretary Rambir Singh on April 29 drew the attention of Arunachal Pradesh’s chief secretary Naresh Kumar towards the allegation.

“This is due to their exclusion from economic packages for vulnerable sections in these difficult times of COVID-19 pandemic…..,” Singh wrote to Kumar asking him to take up the issue on priority.

Related news: Centre, state should make stand clear on Chakma-Hajong refugees: AAPSU

After the ministry’s nudge, the concerned district administration started relief distribution among the poor people from the two communities under the state disaster relief fund.

Meanwhile, DC Changlang said the government has also started transferring ₹3,500 into the bank accounts of migrant workers and students stuck in other states. At least 2,000 people from Chakma communities of Changlang would benefit from it, he added.