Live Law / View in PDF Version

28 June 2020

“Custodial death is one of the worst crimes in a civilised society governed by Rule of Law. Does a citizen shed off his fundamental right to life, the moment a policeman arrests him? Can the right to life of a citizen be put in abeyance on his arrest? The answer, indeed, has to be an emphatic “No”-Supreme Court in D K Basu v State of West Bengal AIR 1997 SC 610.

Independent investigation in a case of custodial death/torture, at least in the initial stages, is a big problem, owing to the obvious fact that the police are called upon to probe against themselves. The Supreme Court had commented about the ‘ties of brotherhood’ within police, which stall fruitful investigation in cases of custodial violence, as follows :

“…rarely in cases of police torture or custodial death, direct ocular evidence of the complicity of the police personnel would be available. Generally speaking, it would be police officials alone who can only explain the circumstance in which a person in their custody had died. Bound as they are by the ties of brotherhood, it is not unknown that police personnel prefer to remain silent and more often than not pervert the truth to save their colleagues” (State of MP vs Shyamsunder Trivedi, 1997).

In many cases, investigation is later handed over to independent agencies like CBI, or Special Investigation Teams, mostly as a result of cases fought by the relatives of the victims. But such a subsequent transfer of probe cannot assure concrete results, if the investigation in the initial crucial stages of evidence collection such as post-mortem, inquest etc., has been manipulated.

To take care of this problem, the law has envisaged a process of parallel Magisterial Inquiry, immediately after the incident.

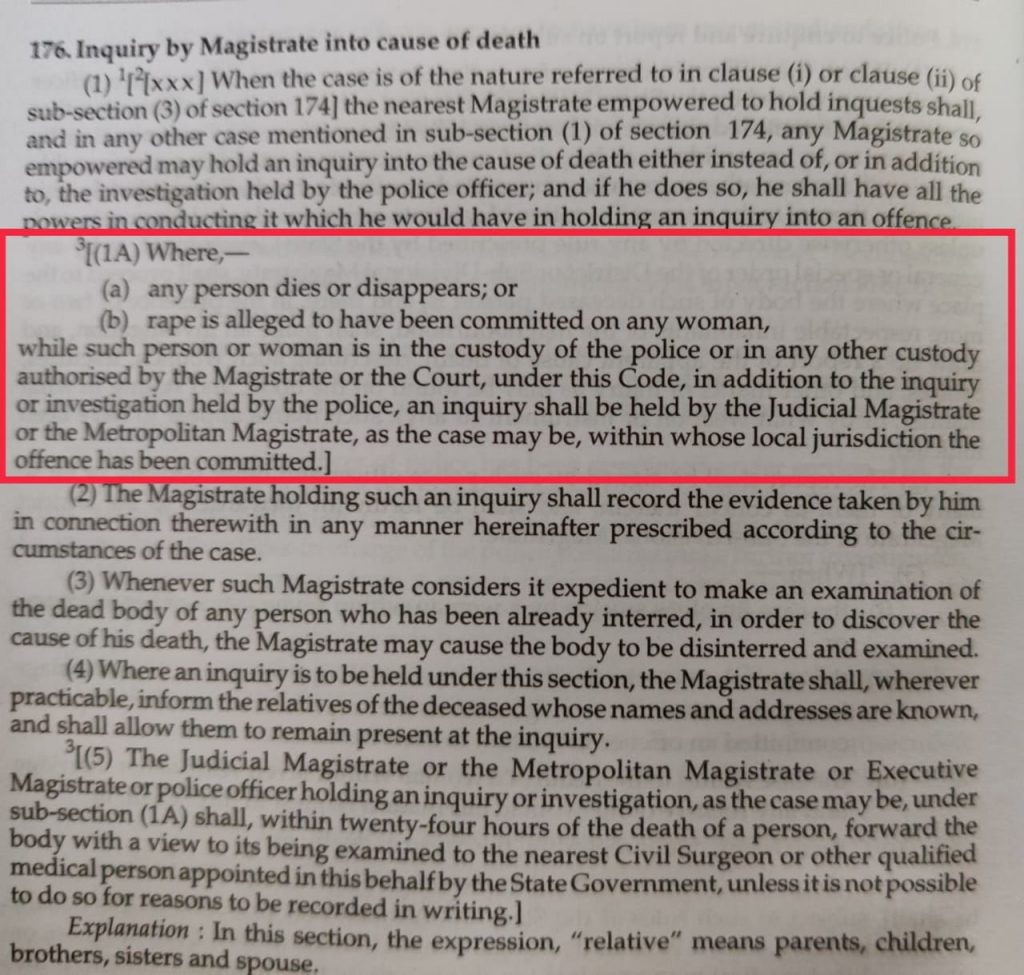

This is as per Section 176(1 A) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, inserted after 2005 amendment to CrPC.

Section 176(1) CrPC states that a Magistrate, who is empowered to hold inquests with respect to an unnatural death, may hold an inquiry into the cause of death in addition to the investigation held by the police officer. This is only a general, empowering provision, giving Magistrate the discretion to hold such an inquiry. Another fact to be noted is that such inquiry can be held either by an Executive Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate.

On the other hand, Section 176(1A) is a special provision to deal with cases of death, disappearance or rape in police custody. The provision says that in such cases, the Judicial Magistrate or the Metropolitan Magistrate, within whose local jurisdiction the offence has been committed, shall hold an inquiry in addition to the inquiry or investigation held by the police.

The section can be broken down as :

- This inquiry is parallel to the police investigation into custodial death/rape/disappearance.

- This inquiry cannot be done by an Executive Magistrate and must be carried out by a Judicial Magistrate.

- This inquiry is mandatory(denoted by the use of word “shall” in distinction with the use of word “may” in Section 176(1)).

Section 176(5), also inserted after 2005 amendment, mandates that the Magistrate holding such inquiry should, within 24 hours of the death of the person, forward the body with a view to it being examined to the nearest Civil Surgeon. If it is not possible to do so, reasons must be recorded in writing.

In 1994, the Law Commission of India, after taking note of abysmal rates of conviction in cases of custodial violence, had recommended the insertion of these provisions – Sections 176(1 A) and 176(5) – in its 152nd report. They were inserted a decade later, as per 2005 amendment.

The National Human Rights Commission has also issued guidelines for Magisterial Enquiry, as per which it should cover the following aspects.

- The circumstances of death

- The manner and sequence of incidents leading to death

- The cause of death

- Any person found responsible for the death, or suspicion of foul play that emerges during the enquiry.

- Act of commission/omission on the part of public servants that contributed to the death

- Adequacy of medical treatment provided to the deceased.

The NHRC has also set a two month deadline for the completion of enquiry by Magistrate.

Non-compliance of Section 176(1A)

Despite the mandatory nature of this provision, its compliance is highly rare.

In January 2020, the Supreme Court had issued notice on a Public Interest Litigation petition seeking a directive to all States/UTs for strict implementation of Section 176(1 A). That PIL filed by human rights activist Suhas Chakma stated that out of 827 cases of death or disappearance of persons in police custody between 2005 and 2017, judicial inquiry was ordered only in 166 cases i.e. 20% of the total cases.

“Section 176 (1 A) since its enactment has been left untouched, remained only in the statute books, and not implemented on the ground with the consequence of rising custodial crimes.”, the plea said.

Even in the Jeyaraj-Bennix custodial deaths cases of Sathankulam, Tamil Nadu, the Madras High Court had to make a suo moto intervention to order enquiry by the Kovilpatti Judicial Magistrate.

Registration of FIR

Registration of FIR in a case of custodial death is mandatory.

The Supreme Court clarified in the decision Lalitakumari vs State of UP (2014) 2 SCC 1 that ‘registration of FIR is mandatory under Section 154 of the Code, if the information discloses commission of a cognizable offence and no preliminary inquiry is permissible in such a situation’.

Even Section 176(1 A) speaks of regular police investigation in cases of custodial death, and the Magisterial Inquiry is envisaged as in addition to police investigation.

As regards the Sathankulam case, the police has not lodged an FIR with respect to the custodial deaths at the time of writing this piece.

The Law Commission of India had foreseen this problem of police delaying lodging of FIR in cases of custodial deaths, and had suggested in its 152nd the insertion of a new provision to enable any person to approach a judicial authority on the failure of police to register FIR.

This was proposed to be inserted Section 154A in the CrPC, reading as follows :

“Section 154A. Notwithstanding anything contained in Section 154:

(1) Any person (including Legal Aid Centre, orNGO, or any friend or relative) aggrieved by a refusal on the part of an officer in charge of a police station to record the information referred to in sub-section (1) of that section in cases relating to custodial offences, may file a petition giving substance of such information:

(a) before the Chief Judicial Magistrate, in case of custodial offences other than those involving death of the victim, or.

(b) before the Sessions Judge, in cases of custodial offences involving death of the victim.

(2) The Chief Judicial Magistrate or the Sessions Judge, if satisfied, on a preliminary enquiry that there is a prima facie case, may himself hold enquiry into the complaint or direct some other Judicial Magistrate or Additional Sessions Judge, as the case may be, to hold enquiry and thereupon direct the ministerial officer of the Court to make a complaint to the competent court in respect of the offence that may appear to have been committed.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in Section 190 of the Code of Criminal Procedure on a complaint made under sub-section (2), the competent court shall take cognizance of the offence and try the same.

(4) The Chief Judicial Magistrate or the Sessions Judge may obtain the assistance of any public servant or authority as they may deem fit in holding the enquiry under sub-section (2).”

The incorporation of this provision, following the recommendations of the Law Commission of India, would have addressed the problem of delay in lodging FIR by setting off the criminal investigation process through judicial intervention at the instance of aggrieved persons or public-spirited parties.

Intimation to NHRC

The National Human Rights Commission had issued general instructions in 1993 that within 24 hours of occurrence of any custodial death, the Commission must be given intimation about it.

All reports including post-mortem, videograph and magisterial inquiry report must be sent within two months of the incident.

Directions to video record and photograph autopsy proceedings

The NHRC has issued guidelines to all the States to video-film the post-mortem examination in cases of custodial deaths and send the cassettes to the Commission.

The aim of video-filming and photography of postmortem examination should be:-

i) to record the detailed findings of the post-mortem examination, especially pertaining to marks of injury and violence which may suggest custodial torture.

ii) to supplement the findings of post-mortem examination (recorded in the postmortem report) by video graphic evidence so as to rule out any undue influence or suppression of material information.

iii) to facilitate an independent review of the post-mortem examination report at a later stage if required.

The Commission, after ascertaining the views of the States and discussing with the experts in the field and taking into consideration the U.N. Model Autopsy protocol, has prepared a Model Autopsy Form for custodial death cases.

Is there need for sanction under Section 197 CrPC to prosecute police officers accused of custodial torture?

The Supreme Court, in Devinder Singh and others vs State of Punjab through CBI, held that protection of sanction under Section 197 CrPc was not available for offences which have no connection with official duties.

In this case, a bench comprising Justices V Gopala Gowda and Arun Mishra upheld the argument of prosecution sanction for prosecution was not required in cases of fake encounter and custodial torture.

“Protection of sanction is an assurance to an honest and sincere officer to perform his duty honestly and to the best of his ability to further public duty. However, authority cannot be camouflaged to commit crime”, the bench said.

The top Court observed that “public servant is not entitled to indulge in criminal activities”, and that the protection under Section 197 CrPC has to be “construed narrowly and in a restricted manner”.

“The offence must be directly and reasonably connected with official duty to require sanction. It is no part of official duty to commit offence”, the bench clarified.

The Court added that to claim protection under Section 197 CrPC, it has to be proved that the act was intrinsically connected with official duties.

“In case the assault made is intrinsically connected with or related to performance of official duties sanction would be necessary under Section 7 97 CrPC, but such relation to duty should not be pretended or fanciful claim”, the Court said.

The Law Commission of India, taking note of the fact that the need for sanction under Section 197 CrPC was raised by accused officers in many cases of custodial torture, had recommended the insertion of an explanation in the said Section as follows:

“For the avoidance of doubts, it is hereby declared that the provisions of this section do not apply to any offence committed by a judge or public servant, being an offence against the human body committed in respect of a person his custody, nor to any offence constituting an abuse of authority”.

But this recommendation made in the 152nd report has not been acted upon.