Newslaundry

20 June 2020

By Chitranshu Tewari

A weekly newsletter to help you track the news media ecosystem and make sense of it.

Welcome to Stop Press by Chitranshu Tewari, a weekly newsletter to break down the trends, innovations and news in the media ecosystem. To get it in your inbox every Saturday, sign up now.

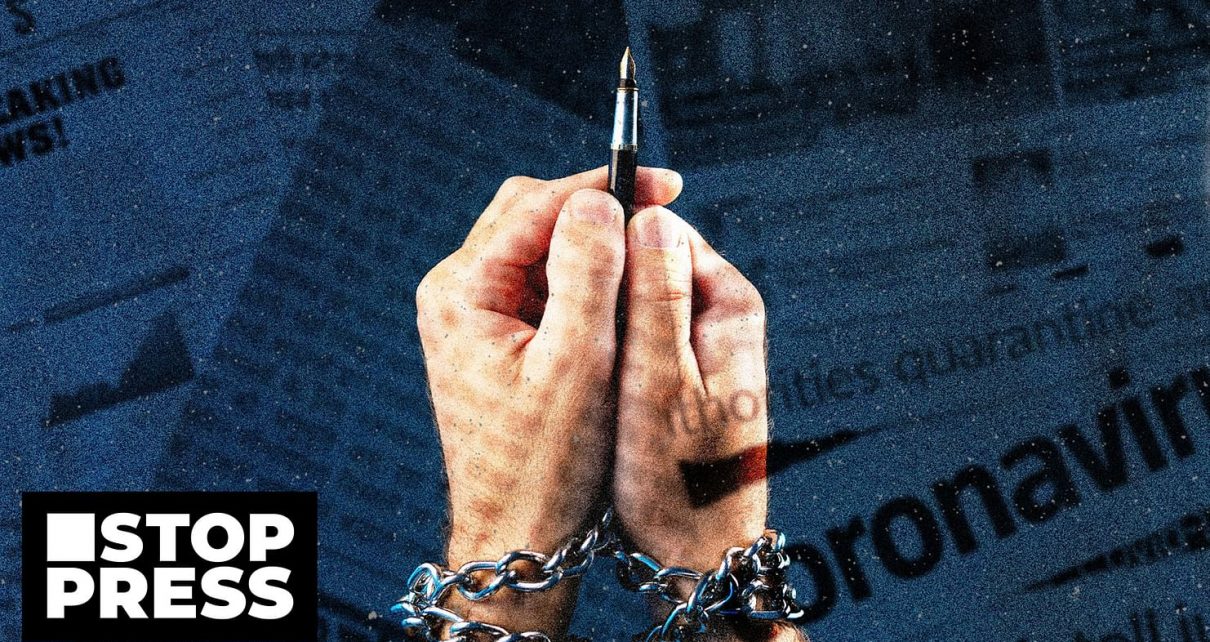

Fifty-five. That’s the number of journalists who have faced arrests, FIRs, intimidation and physical assault ever since the national lockdown was announced on March 25.

And the list seems to be swelling each day.

On Thursday, the Varanasi police booked Scroll’s executive editor, Supriya Sharma, under charges of defamation, negligence to spread infectious diseases, and sections under the SC/ST Act (a non-bailable offense). Why? An FIR was lodged by a Dalit woman quoted in Sharma’s report on the impact of the lockdown in a Varanasi village that was adopted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

It doesn’t take much to uncover the real motivations behind the FIR. How does a ground report, highlighting the hunger faced by people during the lockdown, mock poverty and caste, as alleged by the complainant? Is it a coincidence that the complainant found out about the story only after a police official informed them?

NDTV spoke to the complainant and her son, underlining the gaps between the story and the claims made in the FIR.

.@OnReality_Check | Muzzling the media? Decoding the UP police FIR against https://t.co/EPOcLL2erl pic.twitter.com/SP0r3axHIZ

— NDTV (@ndtv) June 19, 2020

Uttar Pradesh tops the chart

Just like Sharma’s FIR, there have been at least 11 more instances of crackdowns on media persons in Uttar Pradesh — a tally that beats all other states, according to a report by the Rights and Risks Analysis Group, a Delhi-based think tank.

This includes an FIR (filed under the SC/ST Act and Disaster Management Act) against a reporter for his story on mismanagement and negligence at a quarantine centre, a notice by a district magistrate to a newspaper for its story on how Dalits were forced to eat grass due to starvation, and an interrogation of a reporter by a Special Task Force of the police after his report on low-quality PPEs.

Such has been the administration’s enthusiasm to file FIRs that journalists in Fatehpur district conducted a “jal satyagraha” to protest against FIRs slapped on their colleagues.

The news reports that triggered the FIRs and notices leave no doubt that the idea is to intimidate journalists and media houses from anything that makes the state government look bad in its Covid-19 efforts.

Final blow to local media

Local media over the world is facing an existential threat. The vanishing ad revenue accelerated by Covid-19 has already shut local outlets abroad. Back in India, there’s hardly any coverage of local media to know the extent of it.

Local media is, in many ways, a bedrock of any media ecosystem. They reach places that the mainstream or metro-based media never will, uncovering issues that both national TV and dailies have little appetite for.

In such a context, what does the strategic gagging of journalists mean for the local media? While journalists working with major outlets, in cities like Delhi and Mumbai, get an outpouring of support and resources to stand up to the government, local journalists in smaller cities and with lesser-known outlets mostly fend for themselves.

The media needs to further spotlight the attacks on journalists from smaller cities and towns. If anything, their stories deserve even more attention due to the odds they go against to bring us the truth.

It’s clear what danger we are looking at and the message that the government is signalling: that the government will come after you if you make them look bad. Now more than ever, you, the reader, need to support independent media and power ground reports. Subscribe to Newslaundry. You can also read our reports on the gagging of local journalists here, here, here.