Article 14

10 July 2020

By JAYPRAKASH S NAIDU

UP police killing of ganglord VikasDubey and five aides follows a 20-year national pattern: 2,123 Indians died in police custody or a lockup, including those who may or may not have been produced before a court. Judicial inquiries made little difference.

Mumbai: The deaths of a Uttar Pradesh ganglord and five aides in separate alleged firefights with police follow a pattern now evident over two decades: 67% or 1,423 Indians died in police custody or lockup, including those who may or may not have been produced before a court.

At least 700 of 2,123 (33%) deaths in police custody over 20 years to 2018 occurred after accused were remanded to police custody by a magistrate, according to our analysis of National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, as in the case of P Jeyraj and his son J Bennix, who were tortured to death by Tamil Nadu police on 20 June. Dubey and his men were shot before being taken to a magistrate.

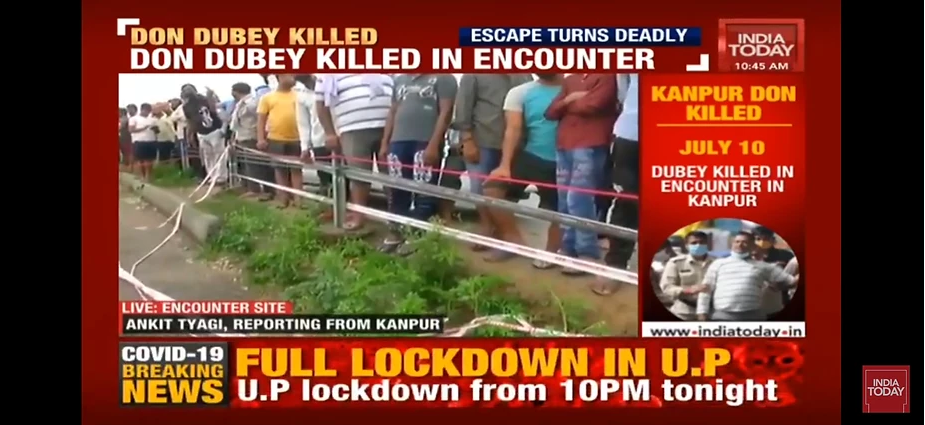

Wanted in 62 criminal cases, Vikas Dubey was shot dead on 10 July 2020 by the UP police, who claimed he tried to escape when the police car carrying him overturned. Since 3 July, five of his aides were similarly shot dead, according to police: trying to escape when a puncture was being fixed; while stealing a car; in a firefight; escaping after robbing the occupants of a car and in a gunfight.

Hours before Dubey was killed, a Mumbai lawyer filed a petition before the Supreme Court seeking “urgent” action before Dubey too faced the same fate as his aides.

Extrajudicial killings in India are almost institutionalised, experts said, because the police still operate with a colonial structure and mindset; possess a “union culture” focussed on exonerating their own instead of punishing excesses; governments protect officers involved in extrajudicial killings by refusing to accord sanction for their prosecution; and public opinion, which lauds such killings.

“The whole system participates in these kinds of things (custodial deaths),” said Prakash Singh, a former UP Director General Police (DGP) and a key advocate of police reforms. “There is a trade union mentality in the force and they protect their colleagues. It’s a failure of supervision and leadership.”

In Majority Of Custodial Deaths, No FIR

The NCRB divides “custodial deaths” into three categories: death in police custody after being remanded to police custody by a court; death in police custody or in a lock up of “persons not on remand”; and death when being taken to court or during court proceedings.

In the 2,123 deaths over two decades to 2018, a first information report (FIR) was filed in no more than 1,017 (47.9%). In the other 1,106 (52%) cases of custodial deaths, a FIR was not filed as, according to police records, suspects died in police custody because of various reasons, such as “illness, during treatment at hospitals, suicides, natural deaths, road accidents or while escaping from police custody”.

A string of prominent cases have revealed many police claims as fabricated, such as Mumbai engineer Khwaja Yunus, who, according to police, escaped from their custody in 2004 and was never found. During a trial, a co-accused revealed Yunus was tortured. The trial of four policemen continues, and despite a chargesheet filed against them by police investigators, they have been reinstated by the Maharashtra government.

The Yunus case effectively ended the era of Mumbai’s “encounter specialists”, officers who claimed to have gunned down suspects in firefights. Later, in some cases, it emerged these officers had placed guns on dead suspects, a common practice, as a Manipur policeman who serially killed people in this manner confessed.

Mandatory Judicial Inquiries Make Little Difference

As we said, in 1,106 custodial deaths no FIRs were registered because official inquiries showed that the police had no role to play in these deaths.

To ensure that those involved in custodial deaths don’t get away due to complicity of colleagues and superiors, a judicial inquiry in every custodial death was made mandatory in 2005.

Section 176 (1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973, was amended to 176 (1a), which made a judicial inquiry mandatory for “custodial deaths, rapes and disappearances in custody”.

“The main reason for replacing a magisterial inquiry into a judicial inquiry (inquiry by judicial magistrate) was that senior policemen, such as assistant police commissioners and IPS (Indian Police Service) officers also have the powers of executive magistrates, and, hence, they may not conduct a fair investigation to shield subordinates,” said Suhas Chakma, a director at the Rights and Risks Analysis Group, a think tank based in Delhi. “The law came into effect in 2006, but till date it is not followed in all cases of custodial deaths.”

Indeed, judicial inquiries were conducted in less than a quarter of 1,385 custodial deaths between 2006 and 2018, according to NCRB data. Chakma has filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court, which on 24 January 2020 asked for responses from the Centre and states.

Governments Reluctant To Prosecute Police

Even if the police do register an FIR after a custodial death, as they did in 1,107 cases over 20 years to 2008 (the latest available data), government sanction for prosecution was given only in 447 or less than half the cases.

This is another example of how the system helps officers accused of custodial crimes. “A prosecution sanction by government authorities is a mandatory requirement before police can file a chargesheet in court against a government servant,” said Chakma. “Hence, even if the investigating agency finds evidence against the cops, if the state DGP or the government—depending upon the rank of the officer—does not provide prosecution sanction, the matter cannot be pursued further.”

The prosecution sanction is a loophole exploited by the government to protect its employees, said Chakma. “The prosecution sanction must be subject to judicial review, otherwise it serves as a major interference in the judicial system and emboldens cops, who believe they can get away with such crimes,” he said.

Even if a government clears prosecution and a chargesheet, few police officers are convicted. Of 477 cops chargesheeted over a decade to 2008, 49 (10%) were convicted, or one in 10.

Many more police officers could be accused in custodial deaths than the data show. Many of the 1,017 FIRs registered against police officers could have multiple accused. There is no information about the charges (murder or culpable homicide or negligence) in these FIRs.

UP Leads The Way In Convicting Police Officers

Of 49 convictions of police officers for custodial deaths nationwide over 20 years, 40 were from UP (three cases in 2010, four in 2009, twenty one in 2006 and twelve in 2005).

Over a decade to 2018, 1,021 custodial deaths were reported, with the highest numbers in Maharashtra (225), Andhra Pradesh (137), Gujarat (115), Tamil Nadu (82) and Madhya Pradesh (79).

Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat did not report any convictions of police officers over 20 years to 2018.

Manisha Sethi, an associate professor at Delhi Jamia Millia Islamia University and a member of the Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association, an advocacy, said the three states with the highest number of custodial deaths, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat, have a long history of encounter killings as law-and-order policy.

“Custodial deaths need more attention,” said Singh, the former UP DGP. “From time to time instructions are issued, but the issue is simple, rules are not followed. In the Tamil Nadu incident, the role of every official including the magistrate needs to be investigated for connivance.”

“The colonial police culture to treat people as subjects instead of serving them has stayed in the police department despite 70 years of Independence,” said former Maharashtra DGP M N Singh. “There is a need to make them (the police) more civilised. Police training is insufficient and not enough attention is given to teaching human rights.”

Others believe Indian data of deaths at the hands of police are under-reported.

“The data on custodial deaths, like that on encounter killings are patchy at best, and represents the tip of the iceberg,” said Sethi. “Custodial deaths following torture are usually dressed up as suicides to avoid scrutiny. Both custodial deaths and encounter killings, which are really a form of custodial killing, operate in the same landscape of impunity: magisterial enquiries are rarely conducted, FIRs are never filed, and no prosecution ever results, in breach of NHRC and Supreme Court guidelines.”

(Jayprakash S Naidu is a freelance reporter based in Mumbai.)